In 1912 Roosevelt Was Running Again for President Which Party Did He Represent This Time?

| Progressive Political party | |

|---|---|

The bull moose was the party's official mascot | |

| Chair | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Founded | 1912 (1912) |

| Dissolved | 1920 (1920) [ citation needed ] |

| Split from | Republican Party |

| Merged into | Republican Party (majority) |

| Succeeded by | California Progressive Party |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Credo | Progressivism New Nationalism |

| Political position | Eye-left to left-fly[i] |

| Colors | Reddish[2] |

| |

The Progressive Party was a third party in the U.s.a. formed in 1912 past former president Theodore Roosevelt after he lost the presidential nomination of the Republican Party to his sometime protégé rival, incumbent president William Howard Taft. The new political party was known for taking advanced positions on progressive reforms and attracting leading national reformers. Subsequently the political party's defeat in the 1912 presidential ballot, it went into rapid decline in elections until 1918, disappearing by 1920. The Progressive Party was popularly nicknamed the "Bull Moose Party" when Roosevelt boasted that he felt "strong as a bull moose" subsequently losing the Republican nomination in June 1912 at the Chicago convention.[3]

Every bit a member of the Republican Party, Roosevelt had served as president from 1901 to 1909, becoming increasingly progressive in the afterwards years of his presidency. In the 1908 presidential election, Roosevelt helped ensure that he would exist succeeded by Secretary of War Taft. Although Taft entered function determined to advance Roosevelt'southward Square Bargain domestic agenda, he stumbled badly during the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act fence and the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy. The political fallout of these events divided the Republican Party and alienated Roosevelt from his one-time friend.[4] Progressive Republican leader Robert Grand. La Follette had already announced a challenge to Taft for the 1912 Republican nomination, but many of his supporters shifted to Roosevelt afterwards the quondam president decided to seek a third presidential term, which was permissible under the Constitution prior to the ratification of the Twenty-second Subpoena. At the 1912 Republican National Convention, Taft narrowly defeated Roosevelt for the political party's presidential nomination. After the convention, Roosevelt, Frank Munsey, George Walbridge Perkins and other progressive Republicans established the Progressive Party and nominated a ticket of Roosevelt and Hiram Johnson of California at the 1912 Progressive National Convention. The new party attracted several Republican officeholders, although about all of them remained loyal to the Republican Party—in California, Johnson and the Progressives took control of the Republican Party.

The party's platform built on Roosevelt'due south Square Deal domestic program and called for several progressive reforms. The platform asserted that "to dissolve the unholy alliance betwixt corrupt business organization and decadent politics is the first chore of the statesmanship of the twenty-four hour period". Proposals on the platform included restrictions on campaign finance contributions, a reduction of the tariff and the establishment of a social insurance organisation, an eight-hour workday and women'southward suffrage. The party was split on the regulation of large corporations, with some party members disappointed that the platform did not contain a stronger telephone call for "trust-busting". Political party members also had dissimilar outlooks on strange policy, with pacifists like Jane Addams opposing Roosevelt's call for a naval build-up.

In the 1912 election, Roosevelt won 27.4% of the popular vote compared to Taft's 23.2%, making Roosevelt the simply third party presidential nominee to terminate with a college share of the popular vote than a major party'due south presidential nominee. Both Taft and Roosevelt finished behind Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson, who won 41.8% of the popular vote and the vast bulk of the electoral vote. The Progressives elected several Congressional and state legislative candidates, but the election was marked primarily by Autonomous gains. The 1916 Progressive National Convention was held in conjunction with the 1916 Republican National Convention in hopes of reunifying the parties with Roosevelt as the presidential nominee of both parties. The Progressive Party collapsed afterward Roosevelt refused the Progressive nomination and insisted his supporters vote for Charles Evans Hughes, the moderately progressive Republican nominee. Near Progressives joined the Republican Party, but some converted to the Democratic Party and Progressives similar Harold L. Ickes would play a function in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's assistants. In 1924, La Follette set up some other Progressive Political party for his presidential run. A tertiary Progressive Party was gear up in 1948 for the presidential campaign of former vice president Henry A. Wallace.

Founding [edit]

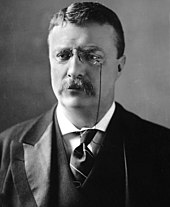

Theodore Roosevelt was the founder of the Progressive Party and thus is often associated with the party

Roosevelt left office in 1909. He had selected Taft, his Secretary of State of war, to succeed him every bit the presidential candidate and Taft easily won the 1908 presidential election. Roosevelt became disappointed by Taft's increasingly conservative policies. Taft upset Roosevelt when he used the Sherman Anti-Trust Deed to sue U.Southward. Steel for an action that President Roosevelt had explicitly approved.[5] They became openly hostile and Roosevelt decided to seek the presidency. Roosevelt entered the campaign tardily as Taft was already beingness challenged by Progressive leader senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin. Most of La Follette'south supporters switched to Roosevelt, leaving the Wisconsin senator embittered.

Nine of the states where progressive elements were strongest had set upwards preference primaries, which Roosevelt won, only Taft had worked far harder than Roosevelt to control the Republican Political party's organizational operations and the mechanism for choosing its presidential nominee, the 1912 Republican National Convention. For example, he bought upwardly the votes of delegates from the southern states, copying the technique Roosevelt himself used in 1904. The Republican National Convention rejected Roosevelt's protests. Roosevelt and his supporters walked out and the convention re-nominated Taft. The next day, Roosevelt supporters met to form a new political party of their ain. California governor Hiram Johnson became its chairman and a new convention was scheduled for Baronial. Most of the funding came from wealthy sponsors, magazine publisher Frank A. Munsey provided $135,000; and George Westward. Perkins, a director of U.S. Steel and chairman of the International Harvester Company, gave $130,000 and became its executive secretary. Roosevelt's family gave $77,500 and others gave $164,000. The total was nigh $600,000, far less than the major parties.[6] [seven]

The new party had serious structural defects. Since it insisted on running complete tickets against the regular Republican ticket in most states, few Republican politicians were willing to support it. The exception was California, where the progressive chemical element took control of the Republican Party and Taft was not even on the November ballot. Just five of the 15 more progressive Republican Senators alleged back up for it. Republican Representatives, Governors, committeemen and the publishers and editors of Republican-leaning newspapers showed comparable reluctance. Many of Roosevelt's closest political allies supported Taft, including his son-in-police force, Nicholas Longworth (though Roosevelt's daughter Alice stuck with her father, causing a permanent chill in her marriage). For men like Longworth, expecting a future of his own in Republican politics, bolting the party would take seemed tantamount to career suicide. However, many independent reformers still signed up.

Historian Jonathan Lurie notes that scholars usually identify Roosevelt as the leader about identified with progressive conservatism. Roosevelt said he had "always believed that wise progressivism and wise conservatism become hand in hand".[eight] All the same, Taft and his supporters often hailed Taft as the model progressive conservative and Taft himself said he was "a believer in progressive conservatism".[9] Four decades later Dwight D. Eisenhower declared himself an advocate of "progressive conservatism".[10]

Progressive convention and platform [edit]

Despite these obstacles, the Baronial convention opened with bang-up enthusiasm. Over 2,000 delegates attended, including many women. In 1912, neither Taft nor Wilson endorsed women'south suffrage on the national level.[11] The notable suffragist and social worker Jane Addams gave a seconding speech for Roosevelt'due south nomination, simply Roosevelt insisted on excluding blackness Republicans from the South (whom he regarded equally a corrupt and ineffective element).[12] Yet he alienated white Southern supporters on the eve of the ballot past publicly dining with black people at a Rhode Island hotel.[13] [xiv] Roosevelt was nominated past acclaim, with Johnson as his running mate.

The main work of the convention was the platform, which gear up forth the new party's appeal to the voters. It included a broad range of social and political reforms long advocated by progressives. It spoke with nigh-religious fervor and the candidate himself promised: "Our cause is based on the eternal principle of righteousness; and even though we, who at present lead may for the time fail, in the end the cause itself shall triumph".[15]

xvi-folio campaign booklet with the platform of the new Progressive Party

The platform'due south primary theme was reversing the domination of politics past business interests, which allegedly controlled the Republican and Democratic parties, alike. The platform asserted:

To destroy this invisible Authorities, to dissolve the unholy alliance betwixt corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first chore of the statesmanship of the mean solar day.[xvi]

To that finish, the platform called for:

- Strict limits and disclosure requirements on political campaign contributions

- Registration of lobbyists

- Recording and publication of Congressional committee proceedings

In the social sphere, the platform called for:

- A national health service to include all existing authorities medical agencies

- Social insurance, to provide for the elderly, the unemployed, and the disabled

- Limiting the ability of judges to order injunctions to limit labor strikes

- A minimum wage law for women

- An eight-hour workday

- A federal securities commission

- Farm relief

- Workers' compensation for work-related injuries

- An inheritance taxation

The political reforms proposed included:

- Women's suffrage

- Direct election of senators

- Primary elections for state and federal nominations

- Easier amending of the Usa Constitution[17] [18] [19]

The platform as well urged states to adopt measures for "direct democracy", including:

- The recollect election (citizens may remove an elected official before the end of his term)

- The referendum (citizens may decide on a law by popular vote)

- The initiative (citizens may advise a law by petition and enact it by pop vote)

- Judicial recollect (when a courtroom declares a law unconstitutional, the citizens may override that ruling past popular vote)[20]

Too these measures, the platform called for reductions in the tariff and limitations on naval armaments by international understanding. The platform also vaguely called for the cosmos of a national health service, making Roosevelt probable the offset major politician to call for wellness care reform.[21]

The biggest controversy at the convention was over the platform section dealing with trusts and monopolies. The convention approved a strong "trust-busting" plank, but Perkins had it replaced with language that spoke merely of "potent National regulation" and "permanent active [Federal] supervision" of major corporations. This retreat shocked reformers similar Pinchot, who blamed it on Perkins. The result was a deep divide in the new political party that was never resolved.[22]

The platform in general expressed Roosevelt'south "New Nationalism", an extension of his earlier philosophy of the Square Deal. He called for new restraints on the ability of federal and state judges forth with a potent executive to regulate industry, protect the working classes and conduct on great national projects. This New Nationalism was paternalistic, in direct dissimilarity to Wilson'southward individualistic philosophy of "New Freedom". Nonetheless, once elected, Wilson's actual programme resembled Roosevelt'south ideas, apart from the notion of reining in judges.[23]

Roosevelt also favored a vigorous foreign policy, including strong military power. Though the platform called for limiting naval armaments, it also recommended the construction of two new battleships per year, much to the distress of outright pacifists such as Jane Addams.[24]

Elections [edit]

1912 [edit]

Roosevelt mixing ideologies in his speeches in this 1912 editorial drawing past Karl K. Knecht (1883–1972) in the Evansville Courier

Roosevelt ran a vigorous campaign, but the campaign was short of money as the business interests which had supported Roosevelt in 1904 either backed the other candidates or stayed neutral. Roosevelt was also handicapped because he had already served nearly ii full terms as president and thus was challenging the unwritten "no 3rd term" rule.

In the terminate, Roosevelt fell far short of winning. He drew 4.1 million votes—27%, well behind Wilson'southward 42%, but ahead of Taft'south 23% (6% went to Socialist Eugene Debs). Roosevelt received 88 electoral votes, compared to 435 for Wilson and 8 for Taft.[25] This was nevertheless the best showing by whatever third political party since the modern ii-political party system was established in 1864. Roosevelt was the simply third-party candidate to outpoll a candidate of an established party.

Pro-Roosevelt cartoon contrasts the Republican Party bosses in back row and Progressive Party reformers in front

Many historians accept concluded that the Republican split was essential to allow Wilson to win the presidency. Others argue that even without the split, Wilson would take won (as he did in 1916).

In addition to Roosevelt's presidential campaign, hundreds of other candidates sought office as Progressives in 1912.

Twenty-i ran for governor. Over 200 ran for U.S. Representative (the verbal number is not clear because there were many Republican-Progressive fusion candidacies and some candidates ran with the labels of ad hoc groups such as "Balderdash Moose Republicans" or (in Pennsylvania) the "Washington Party".)

On October fourteen, 1912, while Roosevelt was candidature in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a saloonkeeper from New York, John Flammang Schrank, shot him, but the bullet lodged in his chest but after penetrating both his steel eyeglass example and a l-folio single-folded copy of the oral communication titled "Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual", he was to evangelize, carried in his jacket pocket. Schrank was immediately disarmed, captured and might have been lynched had Roosevelt non shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed.[26] Roosevelt bodacious the crowd he was all right, then ordered law to accept charge of Schrank and to make sure no violence was done to him.[27] Equally an experienced hunter and anatomist, Roosevelt correctly concluded that since he was not cough blood, the bullet had not reached his lung and he declined suggestions to go to the hospital immediately. Instead, he delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt.[28] He spoke for 90 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attending. His opening comments to the gathered crowd were: "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have simply been shot, but it takes more than than that to kill a Bull Moose".[29] [xxx] [ citation needed ] Afterwards, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt'southward chest muscle, merely did not penetrate the pleura. Doctors ended that it would exist less dangerous to exit it in place than to attempt to remove it and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the remainder of his life.[31] [32] In later on years, when asked almost the bullet inside him, Roosevelt would say: "I practise non mind it any more than if it were in my waistcoat pocket".[33]

Both Taft and Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson suspended their own campaigning until Roosevelt recovered and resumed his. When asked if the shooting would impact his ballot campaign, he said to the reporter "I'chiliad fit every bit a balderdash moose", which inspired the party's emblem.[34] He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the entrada trail. Despite his tenacity, Roosevelt ultimately lost his bid for reelection.[35]

In California, the land Republican Political party was controlled by Governor and Roosevelt marry Hiram Johnson, the vice presidential nominee, so Progressives there stayed with the Republican label (with one exception).

Most of the Progressive candidates were in New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Massachusetts. Only a few were in the South.

The lesser Progressive candidates by and large got between 10% and xxx% of the vote. Nine Progressives were elected to the House and none won governorships.[36]

Some historians speculate that if the Progressive Party had run only the Roosevelt presidential ticket, it might have attracted many more Republicans willing to split their ballot, but the progressive movement was strongest at the state level and so the new party had fielded candidates for governor and state legislature. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the local Republican boss, at odds with state political party leaders, joined Roosevelt's cause. In spite of this, about 250 Progressives were elected to local offices. The Democrats gained many state legislature seats, which gave them 10 boosted U.Southward. Senate seats—they likewise gained 63 U.S. Firm seats.

1914 [edit]

Despite the second-place finish of 1912, the Progressive Party did non disappear at in one case. One hundred xxx-viii candidates, including women,[37] ran for the U.S. Business firm every bit Progressives in 1914 and 5 were elected. Nonetheless, well-nigh half the candidates failed to get more than x% of the vote.[38]

Gifford Pinchot placed 2nd in the Senate election in Pennsylvania, gathering 24% of the vote.

Hiram Johnson was denied renomination for governor as a Republican—he ran as a Progressive and was re-elected. 7 other Progressives ran for governor; none got more 16%.[39] Some state parties remained fairly strong. In Washington, Progressives won a third of the seats in the Washington State Legislature.

1916 [edit]

Louisiana businessman John Thou. Parker ran for governor as a Progressive early in the year as the Republican Political party was deeply unpopular in Louisiana. Parker got a respectable 37% of the vote and was the only Progressive to run for governor that year.[40]

Afterward that year, the party held its second national convention, in conjunction with the Republican National Convention as this was to facilitate a possible reconciliation. Five delegates from each convention met to negotiate and the Progressives wanted reunification with Roosevelt as nominee, which the Republicans adamantly opposed. Meanwhile, Charles Evans Hughes, a moderate Progressive, became the front end-runner at the Republican convention. He had been on the Supreme Courtroom in 1912 and thus was completely neutral on the bitter debates that year. The Progressives suggested Hughes as a compromise candidate, then Roosevelt sent a message proposing conservative senator Henry Cabot Order. The shocked Progressives immediately nominated Roosevelt again, with Parker as the vice presidential nominee. Roosevelt refused to accept the nomination and endorsed Hughes, who was immediately approved by the Republican convention.[41]

The remnants of the national Progressive party promptly disintegrated. Nearly Progressives reverted to the Republican Party, including Roosevelt, who stumped for Hughes; and Hiram Johnson, who was elected to the Senate equally a Republican. Some leaders, such as Harold Ickes of Chicago, supported Wilson.

1918 [edit]

All the remaining Progressives in Congress rejoined the Republican Party, except Whitmell Martin, who became a Democrat. No candidates ran as Progressives for governor, senator or representative.

Afterward years [edit]

Robert One thousand. La Follette Sr. broke bitterly with Roosevelt in 1912 and ran for president on his ain ticket, the 1924 Progressive Party, during the 1924 presidential election.

From 1916 to 1932, the Taft wing controlled the Republican Party and refused to nominate any prominent 1912 Progressives to the Republican national ticket. Finally, Frank Knox was nominated for vice president in 1936.

The relative domination of the Republican Party past conservatives left many former Progressives with no real affiliation until the 1930s, when nearly joined the New Deal Democratic Party coalition of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Balloter history [edit]

In congressional elections [edit]

In presidential elections [edit]

| Election | Candidate | Running mate | Votes | Vote % | Electoral votes | +/- | Outcome of election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912 |  Theodore Roosevelt |  Hiram Johnson | iv,122,721 | 27.iv | 88 / 531 | | Democratic victory |

| 1916 |  Theodore Roosevelt (refused nomination) |  John M. Parker | 33,406 | 0.2 | 0 / 531 | | Democratic victory |

Office holders from the Progressive Political party [edit]

| Position | Proper noun | State | Dates held part |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representative | James Due west. Bryan | Washington | 1913–1915 |

| Governor | Joseph M. Carey | Wyoming | 1911–1912 as a Democrat, 1912-1915 as a Progressive |

| Representative | Walter K. Chandler | New York | 1913–1919 |

| Representative | Ira Clifton Copley | Illinois | 1915–1917 as a Progressive |

| State Representative | Bert F. Crapser | Michigan | 1913–1914 |

| Representative | John Elston | California | 1915–1917 every bit a Progressive, 1917–1921 as a Republican |

| Lieutenant Governor | John Morton Eshleman | California | 1915–1917 |

| Representative | Jacob Falconer | Washington | 1913–1915 |

| Representative | William H. Hinebaugh | Illinois | 1913–1915 |

| Representative | Willis J. Hulings | Pennsylvania | 1913–1915 |

| Governor | Hiram Johnson | California | 1911–1915 as a Republican, 1915-1917 equally a Progressive |

| Representative | Melville Clyde Kelly | Pennsylvania | 1917–1919 as a Progressive, 1919–1935 as a Republican |

| Representative | William MacDonald | Michigan | 1913–1915 |

| Representative | Whitmell Martin | Louisiana | 1915–1919 every bit a Progressive, 1919–1929 equally a Democrat |

| Senator | Miles Poindexter | Washington | 1913–1915 |

| Representative | William Stephens | California | 1913–1917 |

| Representative | Henry Wilson Temple | Pennsylvania | 1913–1915 |

| Representative | Roy Woodruff | Michigan | 1913–1915 |

| State Treasurer | Homer D. Call | New York | 1914 |

| Mayor | Louis Volition | Syracuse, New York | 1914–1916 |

Run across also [edit]

- Committee of 48

- Lincoln–Roosevelt League, the California Progressive Political party in the early 1900s

- Populist Party (U.s.)

- Progressive Party (United states, 1924)

- Progressive Party (U.s., 1948)

- California Progressive Political party

- Oregon Progressive Political party

- Wisconsin Progressive Party

- Minnesota Progressive Party

- Vermont Progressive Party

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ "Pushed Wilson in liberal directions," states Patrick Selmi, "Jane Addams and the Progressive Party Campaign for President in 1912." Periodical of Progressive Man Services 22.2 (2011): 160-190.

- ^ "Enhance Cherry Bandana as Roosevelt Battle Flag; Virtually Emblem of Socialism Gives Color to the New-Born Political party". Idaho Statesman. Boise, Id. June 24, 1912. p. 4.

- Stromquist, Shelton (2006). Reinventing 'The People' . Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 101. ISBN9780252030260.

When the Progressive convention opened in Chicago on Baronial 5, 1912, it reminded many observers of a revival...The social reform community organized a 'Jane Addams chorus,' distributed bright reddish bandanas that became the party's symbol...

- The American Promise. Vol. II. Boston, New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. 2012. p. 674. ISBN9780312663148.

- Stromquist, Shelton (2006). Reinventing 'The People' . Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 101. ISBN9780252030260.

- ^ Morris, Edmund. Colonel Roosevelt. New York: Random Business firm Trade Paperbacks. pp. 215, 646.

- ^ Arnold, Peri E. (October 4, 2016). "William Taft: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Jean Strouse (2012). Morgan: American Financier. Random House. p. 1413. ISBN9780307827678.

- ^ John A. Garraty, Right Mitt Man: The Life of George W. Perkins (1960)

- ^ James Chace (2009). 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs -The Ballot that Inverse the State. Simon and Schuster. p. 250. ISBN9781439188262.

- ^ Jonathan Lurie. William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative (Cambridge University Press, 2012). p. 196.

- ^ Lurie, William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative p ix.

- ^ Günter Bischof. "Eisenhower, the Judiciary, and Desegregation" past Stanley I. Kutler, Eisenhower: a centenary assessment. pp. 98.

- ^ "Balderdash Moose years of Theodore Roosevelt by Theodore Roosevelt Clan". Theodoreroosevelt.org. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ George Eastward. Mowry, "The Southward and the Progressive Lily White Party of 1912". Periodical of Southern History 6#2 (1940): 237–247. JSTOR 2191208.

- ^ Baum, B.; Harris, D. (2009). Racially Writing the Republic: Racists, Race Rebels, and Transformations of American Identity. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 188. ISBN9780822344353.

- ^ Paul D. Casdorph, Republicans, Negroes, and Progressives in the South, 1912-1916 (1981).

- ^ Melanie Gustafson (2001). Women and the Republican Party, 1854–1924. p. 117. ISBN9780252093234.

- ^ Patricia OToole (June 25, 2006). ""The War of 1912," Time in partnership with CNN, Jun. 25, 2006" . Time.com. Archived from the original on July three, 2006. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ See clause # 4.

- ^ Progressive Historians, by Richard Hofstadter, "He (Goodnow) was troubled past the thought that twentieth-century The states was governed by eighteenth-century precepts, and hence was defenseless between a virtually unamendable Constitution and wholly unamendable judges."

- ^ Autonomous Ideals, by Theodore Roosevelt, "We advise to make the process of constitutional subpoena far easier, speedier, and simpler than at present."

- ^ Gary Murphy, "'Mr. Roosevelt is Guilty': Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for Constitutionalism, 1910–1912". Journal of American Studies 36#iii (2002): 441-457.

- ^ "Progressive Party Platform of 1912".

- ^ William Kolasky, "The Ballot of 1912: A Pivotal Moment in Antitrust History". Antitrust 25 (2010): 82+

- ^ Robert Alexander Kraig, "The 1912 Election and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State". Rhetoric and Public Affairs (2000): 363–395. JSTOR 41940243.

- ^ Gustafson (2001). Women and the Republican Political party, 1854-1924. p. 117. ISBN9780252093234.

- ^ Congressional Quarterly'south Guide to U. South. elections. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Inc. 1985. pp. 295, 348.

- ^ "The Balderdash Moose and related media". Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

to make sure that no violence was done.

- ^ Remey, Oliver East.; Cochems, Henry F.; Bloodgood, Wheeler P. (1912). The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Progressive Publishing Company. p. 192.

- ^ "Medical History of American Presidents". Doctor Zebra. Retrieved September fourteen, 2010.

- ^ "Excerpt", Detroit Free Printing, History buff .

- ^ "It Takes More than That to Kill a Bull Moose: The Leader and The Cause". Theodore Roosevelt Association. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Roosevelt Timeline". Theodore Roosevelt. Retrieved September xiv, 2010.

- ^ Timeline of Theodore Roosevelt'southward Life by the Theodore Roosevelt Clan at www.theodoreroosevelt.org

- ^ Donavan, p. 119

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September xix, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create every bit title (link) - ^ "Justice Story: Teddy Roosevelt survives assassinator when bullet hits folded speech communication in his pocket". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved Oct 14, 2013.

- ^ Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.Due south. elections (1985), pp. 489–535, 873–879

- ^ "A Kansas Woman Runs for Congress". The Independent. July xiii, 1914. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U. Southward. elections (1985), pp. 880–885

- ^ Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U. Southward. elections (1985), pp. 489–535

- ^ Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U. South. elections (1985), p. 503

- ^ Fred L. State of israel, "Bainbridge Colby and the Progressive Party, 1914–1916". New York History 40.1 (1959): 33–46. JSTOR 23153527.

Further reading [edit]

- Broderick, Francis L. Progressivism at risk: Electing a President in 1912 (Praeger, 1989).

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs—the Election That Inverse the Land (2004).

- Cowan, Geoffrey. Let the People Dominion: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary (2016).

- Delahaye, Claire. "The New Nationalism and Progressive Bug: The Break with Taft and the 1912 Entrada," in Serge Ricard, ed., A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt (2011) pp. 452–467. online.

- DeWitt, Benjamin P. The Progressive Movement: A Non-Partisan, Comprehensive Give-and-take of Electric current Tendencies in American Politics (1915).

- Flehinger, Brett. The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2003).

- Gable, John A. The Bullmoose Years: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Political party. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Printing, 1978.

- Gould, Lewis L. Four hats in the ring: The 1912 election and the nascence of modernistic American politics (University Press of Kansas, 2008).

- Jensen, Richard. "Theodore Roosevelt" in Encyclopedia of Third Parties (ME Sharpe, 2000). pp. 702–707.

- Kraig, Robert Alexander. "The 1912 Ballot and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State". Rhetoric and Public Affairs (2000): 363–395. JSTOR 41940243.

- Milkis, Sidney M., and Daniel J. Tichenor. "'Directly Democracy' and Social Justice: The Progressive Political party Campaign of 1912". Studies in American Political Development viii#2 (1994): 282–340.

- Milkis, Sidney M. Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party, and the Transformation of American Democracy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

- Mowry, George E. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Mod America. New York: Harper and Row, 1962.

- Painter, Carl, "The Progressive Party In Indiana", Indiana Magazine of History, vol. sixteen, no. 3 (Sept. 1920), pp. 173–283. JSTOR 27785944.

- Pietrusza, David, "TR's Last War: Theodore Roosevelt, the Great State of war, and a Journey of Triumph and Tragedy". (Guilford [CT]: Lyons Press, 2018).

- Pinchot, Amos. What's the Thing with America: The Meaning of the Progressive Motion and the Rise of the New Political party. northward.c.: Amos Pinchot, 1912.

- Pinchot, Amos. History of the Progressive Party, 1912–1916. Introduction by Helene Maxwell Hooker. (New York University Printing, 1958).

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt Ed. Lewis L. Gould. (Upward of Kansas, 2008).

- Selmi, Patrick. "Jane Addams and the Progressive Party Campaign for President in 1912". Journal of Progressive Human Services 22.2 (2011): 160–190.

External links [edit]

- editorial cartoons Archived Feb 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- TeddyRoosevelt.com: Bull Moose Information

- 1912 platform of the Progressive Party Archived September 22, 2011, at the Wayback Motorcar

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_Party_(United_States,_1912)#:~:text=1912%20election&text=The%20Progressive%20Party%20was%20a,incumbent%20president%20William%20Howard%20Taft.

0 Response to "In 1912 Roosevelt Was Running Again for President Which Party Did He Represent This Time?"

Post a Comment